Ultimately, those of us who consider ourselves software engineers, like all engineers, are in the business of building useful things.

Of course, engineers need tools. Civil engineers have dump trucks, trenching machines, and graders. Mechanical engineers have CAD/CAM software. And we have integrated development environments (IDEs), configuration management tools, automated unit testing and functional regression testing tools, and more. Many great testing tools are available, and some of them are even free. But just because you can get a tool, doesn’t mean that you need the tool.

When you get beyond the geek-factor on some tool, you come to the practical questions: What is the business case for using a tool? There are so many options, but how do I pick one? How should I introduce and deploy the tool? How can I measure the return on investment for the tool? This article will help you uncover answers to these questions as you contemplate tools.

Let’s start with the business case. Remember: without a business case, it’s not a tool, it’s a toy. Often, the business case comes down to one or more of the following:

There’s no way to perform some activity without a tool, or, if it is done without a tool, it won’t be done very well. If the benefits and opportunities of performing that activity exceed the costs and the risks associated with the tool, there’s a business case.

The tool will allow you to substantially accelerate some activity you need to perform as part of some project or operation. If that activity is on the critical path for completion of that project or operation, and the benefits and opportunities of accelerating the completion of that project or operation exceed the costs and the risks associated with the tool, there’s a business case.

The tool will allow you to reduce the manual effort associated with carrying out some activity. If the benefits and opportunities from reducing the effort (over some period of time) exceed the costs and the risks associated with the tool (including the effort associated with acquiring, implementing, and maintaining the tool and its various enabling components), there’s a business case.

There can be other business cases, but one or more of these will frequently apply. Sometimes the business case masquerades as something else, such as improving consistency of tasks or reducing repetitive work, but notice that these two are actually the first and last bullet items above, respectively, if you consider them carefully.

Once you’ve established a business case, you can select a tool. With the internet, it is easy to find candidate tools. Before you start that, consider the fact that you are going to live with the tool you select for a long time – if it works – and potentially spend a lot of money on it. So, I recommend that you consider tool selection as a special project, and manage it that way. Form a team to carry out a tool selection. Identify requirements, constraints, and limitations. At this point, start searching the Internet to prepare an inventory of suitable tools. If you can’t find any, then perhaps you can find some open source or freeware constituent pieces that could be used to build the tool you need. Assuming you do find some candidate tools, you should perform an evaluation and, ideally, have a proof-of-concept with your actual business problem. (Remember, the vendor’s demo will always work, but you don’t learn much from a demo about how the tool will solve your problems.) With that information in hand, you’re ready to choose a tool.

Once you’ve chosen the tool, it’s time to pilot the tool and then deploy it. In the pilot, select a project that can absorb the risk associated with the piloting of a tool.

Your goals for the pilot should include the following:

- To learn more about the tool and how to use it.

- To adapt the tool, and any processes associated with it, to fit your other tools and your organization.

- To devise standard ways of using, managing, storing and maintaining the tool and its assets.

- To assess the return on investment (more on that later).

Based on what you learned from the pilot, you’ll want to make some adjustments. Once those adjustments are in place, you’ll want to proceed to deployment of the tool.

Here are some important ideas to remember for deployment:

- Deploy the tool to the rest of the organization incrementally, rather than all at once, if at all possible. In some cases, as for tools required for regulatory compliance, you might not have this luxury, but be sure to manage the risks associated with a rapid roll-out if you must do so.

- Adapt and improve the software engineering processes to fit use of the tool. The tool should effect changes in your processes; otherwise, how could you become more effective and efficient?

- Provide training and mentoring for new users. Be sensitive to the possible learning-curve issues that a new tool can create, and manage the risks that would be created by misuse of the tool.

- Define tool usage guidelines. Some simple explanations – say on a company wiki or in a recorded internal webinar-style lunch-and-learn – can really help people use the tool properly.

- Learn ways to improve use of the tool continuously. Especially in early deployment, you’ll find opportunities and problems the pilot didn’t reveal. Be ready to address those, and to gather a repository of lessons learned (perhaps again in wikis or recorded webinars).

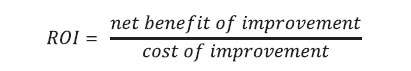

Finally, let’s address this question of return on investment (ROI). For process improvements (including introduction of tools), we can define ROI as follows:

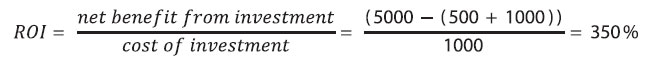

This question of net benefit returns us to where we started: business objectives. Any meaningful measure of return on investment has a strong relationship with the objectives initially established for the tool. Let’s look at an example. Suppose you have developers who currently use manual approaches for code integration and unit testing. This consumes 5,000 person-hours per year. With the tool, one developer will spend 50% of their time as integration/test toolsmith, using Hudson and other associated tools to automate the process. By doing so, developer effort for this process will shrink to 500 person-hours (plus the 50% of the personyear for the toolsmith). So, ROI is:

Notice that, in this case, since the tools are free, I did the calculation entirely using person hours. Sometimes, with commercial tools, you have to perform this whole calculation in dollars or whatever your local currency is.

As software testers, we want to help our organization build useful software, and tools can make us more effective and efficient in doing so. Before we start to use a tool, we should understand the business objectives the tool will promote. Understanding the business case will allow us to properly select a tool. With the tool selected we can then go through one or more pilot projects with the tool, followed by a wider deployment of the tool. As we deploy – and after we deploy – we should plan to measure the return on investment, based on the business case. By following this simple process, you can not only achieve success with tools – you can prove it, using solid ROI numbers.

About the Author

Rex Black – President and Principal Consultant of RBCS, Inc

Rex Black – President and Principal Consultant of RBCS, Inc

With a quarter-century of software and systems engineering experience, Rex specializes in working with clients to ensure complete satisfaction and positive ROI. He is a prolific author, and his popular book, Managing the Testing Process, has sold over 25,000 copies around the world, including Japanese, Chinese, and Indian releases. Rex has also written three other books on testing – Critical Testing Processes, Foundations of Software Testing, and Pragmatic Software Testing – which have also sold thousands of copies, including Hebrew, Indian, Japanese and Russian editions. In addition, he has written numerous articles and papers and has presented at hundreds of conferences and workshops around the world. Rex is the immediate past president of the International Software Testing Qualifications Board and the American Software Testing Qualifications Board.